Stuttgart City Museum in the Wilhelmspalais

Stuttgart City Museum in the Wilhelmspalais, 2017

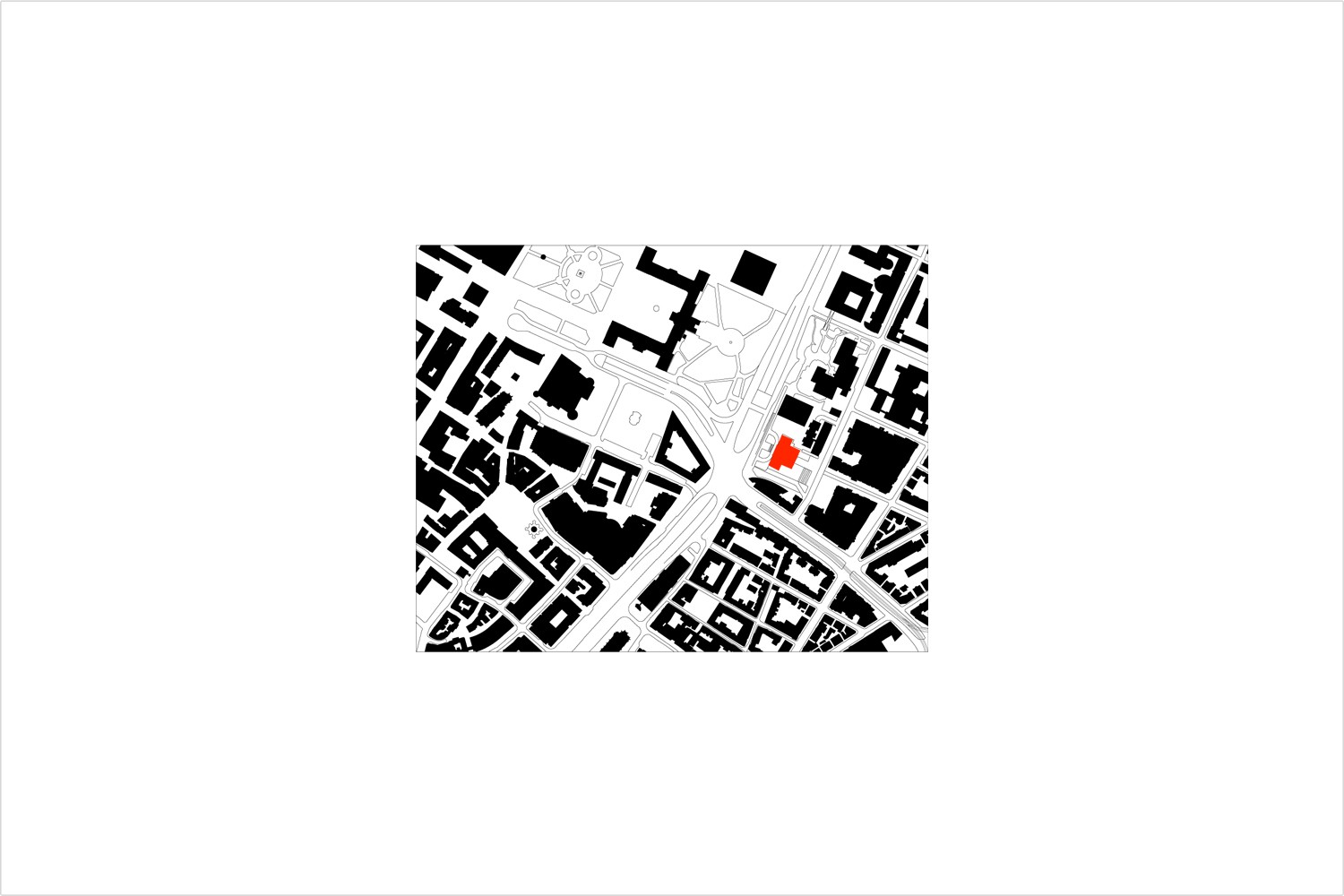

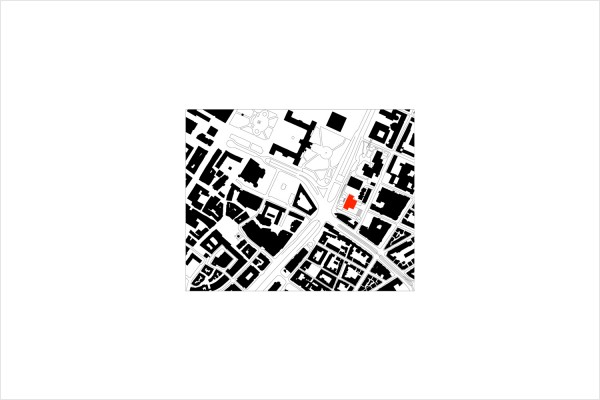

Giovanni Salucci was born in Florence in 1769, trained as an architect, and from 1817 onward, served as the court architect to King Wilhelm I of Württemberg. His works include the Grabkapelle auf dem Rotenberg (Sepulchral chapel on Württemberg hill), Schloss Rosenstein (Rosenstein Palace), and the Wilhelmspalais (King Wilhelm’s Palace), built in 1834. These three buildings, all in Palladian style, are distinguished by their excellent architectural and urbanistic qualities. Salucci’s flair for positioning his works so as to make them widely visible throughout the city and his precise elaboration of these projects in plan and section are characteristic hallmarks. Essentially, his buildings can be understood only in relation to the respective urban situation as a whole. Unfortunately, with the exception of the sepulchral chapel, this circumstance – namely, the unbroken synergy between the city and the building typology – no longer exists due to post-war reconstruction. The public space as a constitutive framework for individual buildings was almost entirely lost by the subsequent destruction caused by reconstruction. This pertains most notably to the Wilhelmspalais, which, in the 19th century, marked the corner of what was then most beautiful urban space in Stuttgart. The groundwork for it had been laid by Nikolaus von Thouret, with a city plan in which he set Neckarstraße at right angles to the Planie, a tree-lined esplanade. While the Planie was to have two palatial structures to the right and left, the Hohe Karlsschule and the orphanage opposite it, Thouret envisioned Neckarstraße as being lined with important buildings for the education and culture of the kingdom. With the Wilhelmspalais, Salucci marked not only the end of the axis of the Planie, but, at a right angle to it, the starting point for the northeasterly development of Neckarstraße.

In the palace itself, we see the two directions asserted by recurring rectangular shapes. They are, however, likewise a reflection of the use. King Wilhelm I wanted the building as a residence for his two daughters. Thus the bilateral arrangement of the stairs, left and right of the large through-hall, reflects the shared aspect as well as the separation of spaces for both residents.

However, only one of the two daughters, Marie, lived in the building. After her death, the building remained in family ownership until 1924, when it was sold to the Württembergian clearing house and savings bank association, ultimately passing into the possession of the city in 1929. Initially destined to house a Zeppelin museum, the Deutsches Auslands-Institut (DAI, German Foreign Institute) instead moved into the palace, which from 1936 to 1944 housed an exhibition titled “Ehrenmal der deutschen Leistungen im Ausland” (Memorial to German achievements abroad).

According to contemporaneous records, 57.5 per cent of the built fabric had been damaged in the war. The spatial structure of the walls is still clearly recognisable on aerial photographs from the 1950s, so according to today’s criteria, restoration would have been quite possible.

In 1961 it was decided to replace the old interior spaces with a new municipal library behind the old façades. The architect, Wilhelm Tiedje, planned to provide access to the building mainly from the rear, via a bridge. In place of the two open stairs to either side of the former hall, he designed a central staircase that he set directly on the middle axis, behind the former main entrance. In other respects, the new internal layout followed the functional needs of the library, in terms of the positioning of the floor levels as well as the clear disposition of the plan, henceforth with closed walls. Thus the unity of the urban configuration in plan, as described above, was lost.

The reversal of the circulation concept – with entry from behind and the stairs occupying the central axis – may well have been a consequence of traffic planning, Charlottenplatz, rebuilt as a multilevel transportation structure, split the visual and pedestrian connection between Planie and Wilhelmspalais. Given the acceptance of changes to the street that favoured vehicular traffic, the solution for the library’s design was a logical outcome. The ensuing destruction of the urban fabric was probably viewed as a secondary problem, or one chose not to see it at all.

Independent of these enormous interventions in the cityscape, whether rightly or not, the public opinion has mostly changed on this point as a result of criticism of the effects of the city’s reconstruction. The discussion about the spatial qualities of European cities, which has also been taking place in Stuttgart since the early 1990s, played a major role in the competition for the reuse of the Wilhelmspalais. Hence we first dealt with the question of how, in the process of converting the building into the City Museum, the grounds and the internal structure could be used to reinforce Salucci’s original design concept. In front of the palace, that meant removing the walls facing Konrad Adenauer Straße and building a large series of stairs to restore a continuous flow of space that unites the street, sidewalk, entry drive, and entrance hall. Over the long term, we saw the removal of the tunnel entrances to the Planie as equally worthy of consideration, as is the desire to connect the Kunstmuseum and the Wilhelmspalais, as the two ends of the Planie, into an urban spatial unit.

Inside, the concept also requires removal of the central stair, which would be replaced by circulation elements on both sides of the axis, in a position similar to what had been drawn and built by Salucci. By taking out the walls on the ground floor, we wanted to open up the floor plan in order to properly reflect the idea of the former central hall and, in addition, the continuous visual axis passing through the building, which once linked the city and garden sides, also from outside. We achieved all this without reconstruction of the old, but rather as a clear interpretation of the classicistic concept, which, even today, can be seen as exemplary in dealing with the city and the building. In short, we replaced Tiedje’s construction within the Salucci walls with an entirely new inner building.

By so doing, the heights between floors could be changed, albeit in coordination with the façade openings in the existing exterior walls. Thus we were able to insert an additional level into the outer shell. There, on the mezzanine, the gained storey height is relatively low but suitable for accommodating the toilet facilities and cloakrooms.

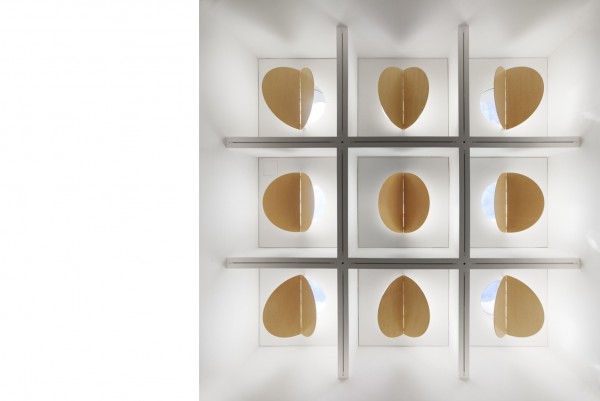

Thanks to the removal of the old/new construction (from the 1960s), we were able to insert two central double-storey halls into the centre of the palace. Not as in the original building for the daughters, but in keeping with the idea of the central emphasis of the Palladian layout. The space below forms the heart of the entrance hall, and above, it is a toplit hall whose skylights are fitted with operable flaps to control the light. In the basement, which could also be re-dimensioned in size and height, we wanted to create openings to the garden. But due to historical preservation concerns as well as reasons of cost, this was not possible.

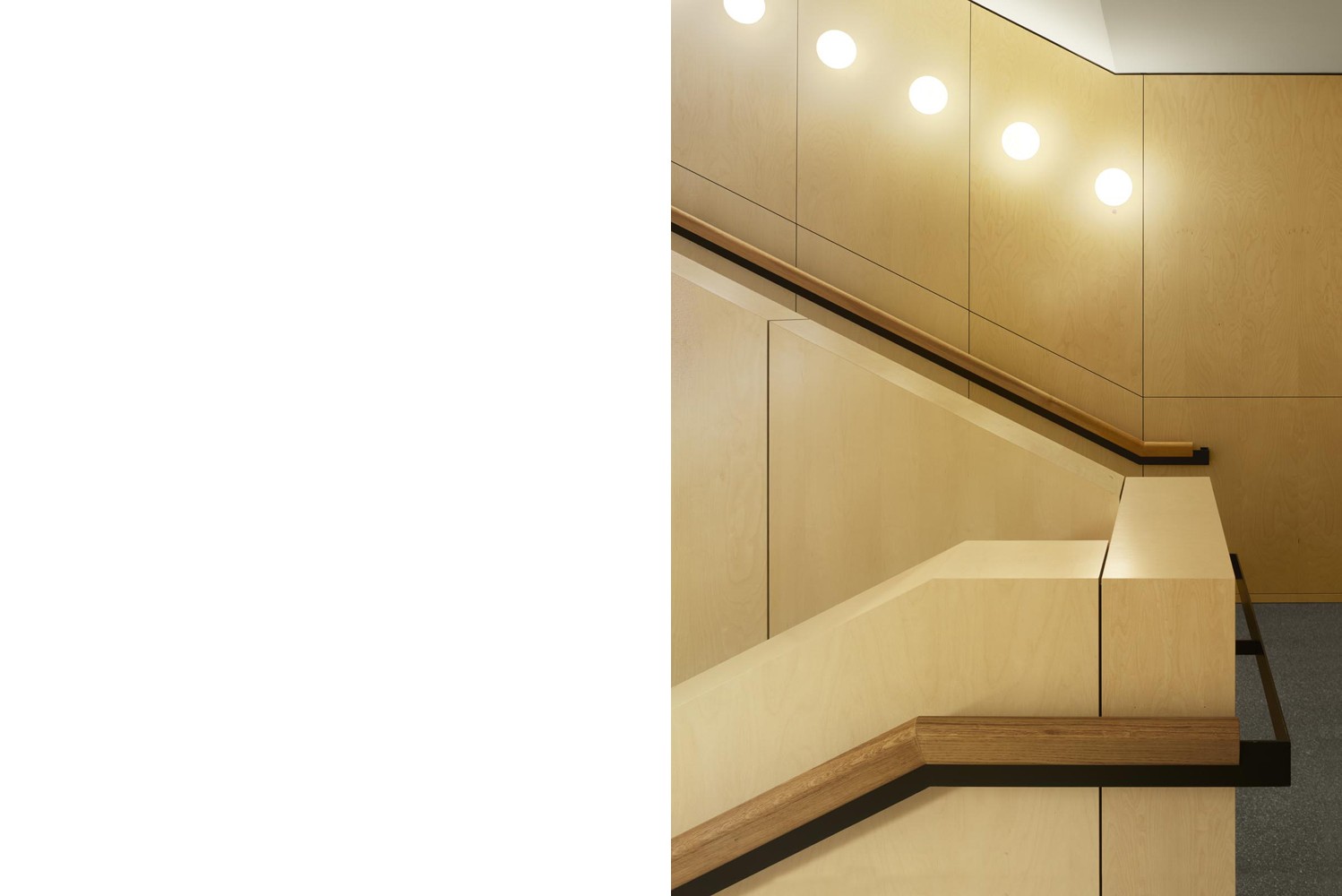

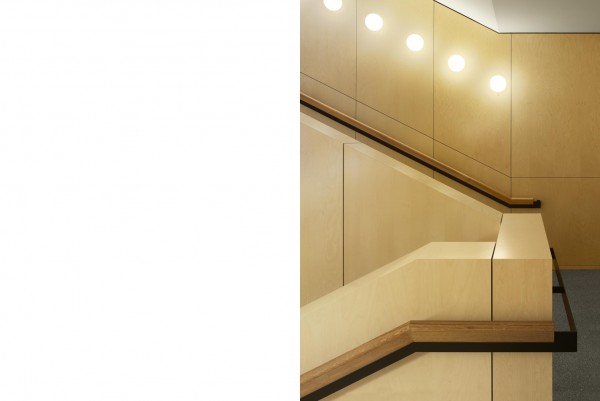

Construction of the entire self-supporting reinforced concrete structure necessitated securing the old façades, which was by no means easy. It was impressive to see this engineering feat during the time when the outer walls, like an empty box, were waiting to be filled again with rooms. Because an additional storey was being inserted, all the building services – the wiring, piping and equipment – had to be routed within the space between the Salucci façade and the enclosing walls of the rooms. Therefore we chose a lightweight enclosure of wood construction, which, like a birchwood treasure chest, envelops the interior spaces. This material establishes the chromatic impression of the building. The windows reveal a view of the city past their deep soffits. They are set into the wooden surfaces like display cases.

Entering the palace via the (hopefully soon to be built) stairs from the street, you only have to go a few metres to stand in the centre of the lower hall. To the left you reach the lecture theatre, and to the right, an equally large salon intended for discussions about current issues and developments in the city. In the hall itself are a café on the left and the reception and information desk on the right. Behind it will be the museum shop, and on the opposite side, the kitchen for the café. In between, the route leads out again, onto the bridge that spans over the garden towards Urbanstraße. The previous structure from the Tiedje era was dilapidated; it has been redesigned to also accommodate outdoor seating for the café.

Back in the main hall, you encounter the two new stairways heading upstairs, where you first reach the surrounding gallery with a view into the hall. There on the mezzanine, as previously mentioned, are the cloakrooms and toilets. One level higher is the permanent exhibition, conceived by the office jangled nerves. There, it is possible to walk around the stair enclosures, and you can also step out onto the balcony overlooking the Planie. On the uppermost level you reach the space for temporary exhibitions and, next to it, the administrative offices.

The building’s design takes into account that in the long term, the rooms can also be used for other purposes. The museum concept now being implemented is not limited to the familiar areas for permanent and temporary exhibitions. The basement level, for instance, is being fit out to house an urban laboratory (“Stadtlabor”) in which visitors, especially children, can become acquainted in a playful way with the expansive areas that make up the city. The entrance level is dedicated to encounters with and exploration of the themes of the city. It could become the “living room” of the city. Most importantly, the palace is intended to encourage people to use it not just as a museum that only helps us to remember the past, but also as a vibrant place within the city dedicated to this city’s past, present, and a possible future.

Client:

Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart

represented by Technisches Referat, Hochbauamt

Occupant:

Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart, Kulturamt

Architects:

Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei Architekten, Stuttgart

Team:

Klaus Hildenbrand, Benedikt Nauder, Anna Noack, Heiko Müller

Project management:

DU Diederichs, Munich

Exhibition:

jangled nerves, Stuttgart

Structural Engineering:

Ingenieurbüro Knippers Helbig, Stuttgart

Engeneering for technical building facilities:

Rentschler und Riedesser, Filderstadt

Electrical engineering:

Raible + Partner, Stuttgart

Structural physics:

Bobran Ingenieure, Stuttgart

Fire protection planning:

Halfkann + Kirchner, Stuttgart

Competition:

2010 – 1st prize

Construction period:

2014 – 2017

Gross floor area:

9.250 m2

Cubature:

36.550 m3

Effective Area:

7.350 m2

Location:

Konrad-Adenauer-Straße 2, 70173 Stuttgart, Germany

Awards

Beispielhaftes Bauen Stuttgart 2015-2019

Architektenkammer Baden-Württemberg

Nominee DAM Prize 2020

Deutsches Architektur Museums (DAM) Frankfurt

Hugo-Häring-Auszeichnung und Publikumspreis 2017

BDA Stuttgart Mittlerer Neckar

Publications

Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei 2

Lederer, Arno / Ragnarsdóttir, Jórunn / Oei, Marc (Hg.)

Jovis Verlag Berlin 2021

Baukultur Baden-Württemberg / Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Wohnungsbau Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart (Hg.): Staatspreis Baukultur Baden-Württemberg 2020

Stuttgart 2020

av edition/Edith Neumann im Auftrag der Landeshauptstadt Stuttgart (Hg.):

Das Wilhelmspalais – Von der königlichen Residenz zum Museum für Stuttgart

12|2019

dom publishers (Hg.):

Architekturführer Deutschland

11|2019

dom publishers (Hg.):

Architekturführer Stuttgart

12|2018

Amber Sayah (Hg.):

Architekturstadt Stuttgart

Chr. Belser Gesellschaft für Verlagsgeschäfte GmbH & Co. KG in Kooperation mit der Stuttgarter Zeitung Stuttgart 2018

ISBN 978-3-7630-2803-0

Domus (deutsche Ausgabe)

07/08 | 2018

AIT

04 | 2018

db

10 | 2017

Stuttgarter Zeitung

19.09.2017

Stuttgarter Zeitung

14.09.2017

Photos

Roland Halbe, Stuttgart