Restoration of Hospitalkirche Stuttgart

Restoration of Hospitalkirche Stuttgart, 2017

To be clear from the outset: we weren’t really enamoured with the Hospitalkirche.

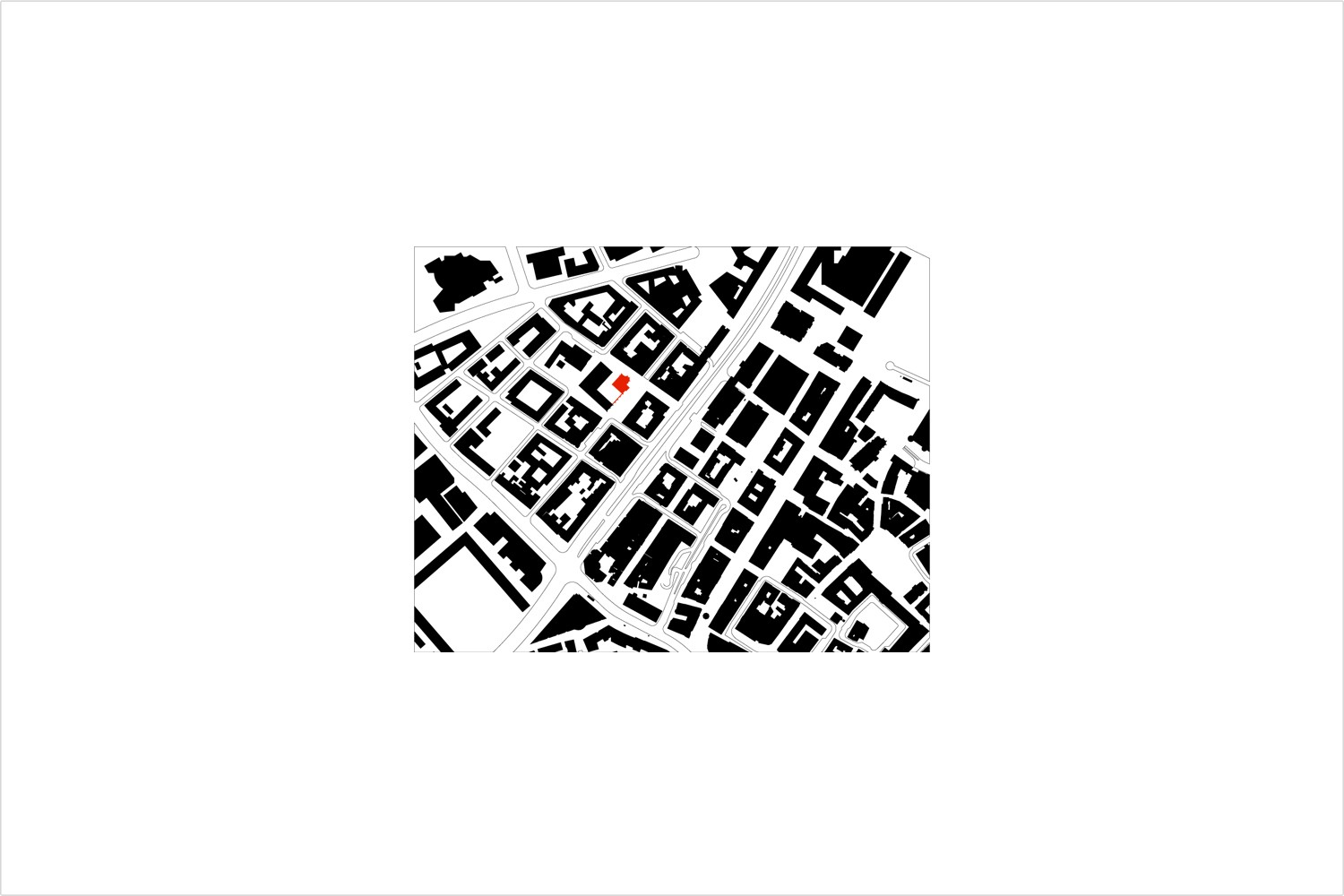

In the urban setting it had a quite respectable presence, with its chancel, steeple, and the remains of the southern wall of the former nave. Here, you could still sense the grandeur of the church; one was reminded of the erstwhile urban church, an architectural anchor in a densely built environment. But if you went through the portal of the ruinous wall, you found yourself before the front wall of the church, which stood out because of its completely different design. While it was still possible to recognise the dignity and extent of the chancel and the nave, this impression vanished when you stood in front of the utterly flat facade, which had nothing in common with the original pointed arch windows nor with the spatial depth and the accompanying play of light and shadow of the Gothic architecture. There, it was and is clear at first glance that behind the high windows was once a large and impressive church interior. By contrast, the entry facade from the post-war era left you with uncertainty.

With the Hospitalkirche, it is not only a matter of making repairs, but also a question of how to deal with what we see here as a dichotomous heritage: the Gothic church on the one hand, and the post-war partial reconstruction on the other.

We wanted to tackle the contradiction and what was, in our opinion from a design standpoint, the mediocre treatment of the wartime ruin.

A tight budget meant that the architectural interventions could only affect details. Thus the question was if and how the attitude of the “Heimatschutzstil“ could be mitigated with minor interventions. In any case, the goal was to eliminate the church interior’s musty and dark look and feel, to bring light into the space, and to try to enlarge the openings along the western facade.

When designing the Hospitalhof, we had already responded to the ground plan of the former nave by planting slender trees where the church piers were formerly located. The idea was to establish a visual connection between the interior and the exterior, to call to mind the merger of the two spaces: the nave and the chancel. For that reason, in the middle of the original building we designed a generously glazed vestibule that is meant to simultaneously facilitate new and improved access to the church space itself.

The biggest structural intervention was to be the demolition of the lower gallery on the western side, combined with removal of the outer balcony. The goal here was not only to provide significantly better natural light for the interior space, but also to make the space itself more generous and to restore, as much as possible, the spatial volume of the chancel. Light now also comes directly into the church through the enlarged windows on the “upper floor”. Behind the glazing are glass prisms that diffract the light, so when the position of the sun is right, a play of colour on the floor and walls awaits.

Because we had removed the lower gallery, the organ loft had to be supported by new brackets and two slim concrete columns.

The desire to remove the closely grouped church benches was in accord with the need to technically upgrade the heating. Thus we were able to install underfloor heating across the entire area, which is now covered by ground-finish mastic asphalt flooring. In the chancel you see how it is actually possible to achieve spatial improvement through small measures: alone the removal of the heavy altar can make for a more pleasant spatial impression. A new altar of lighter materials shall find its place more in the centre of the church.

A new coat of paint on the wall and ceiling of the side aisle will, in our anticipation, be an inexpensive but extremely effective measure. Heretofore in the same light-toned colour as the church interior walls as a whole, the new, midnight-blue colour of the side aisle will give it a different spatial impact. This pertains also to the strengthening of the chancel’s longitudinal axis as it had determined the volume before the war, without necessitating any further structural interventions. The contrast, which serves to clearly define the architecture, is achieved by cleaning the vaulting and by making the wall in the nave itself lighter in tone.

The previously poor artificial lighting of the interior will be fundamentally improved by replacing the existing wall-mounted light fixtures with freely hanging pendant luminaires. These also serve to brighten the vaulted ceiling.

The cost-conscious approach, combined with the close collaboration of the client, the advisory board, and all the planners, made it possible to include painting of the exterior wall within the given budget. Changing the Hospitalkirche for the positive and giving it a more modern character through small, economical interventions is also part of the project. The balancing act between costs, monument conservation concerns, legal requirements, and functional improvement should lead to a modest yet noble and refreshing change. It was not a great feat that was needed, but an answer to the question of how architecture can help ensure that you can look forward to visiting the church. The great feat: that was the Gothic church itself. It is a part of history and we wanted to help make it better understood.

Client:

Evangelische Gesamtkirchengemeinde, Stuttgart

Architects:

Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei Architekten, Stuttgart

Team:

Johannes Steiner, Philip Gengenbach

Project Management:

nps Bauprojektmanagement GmbH, Stuttgart

Structural Engineering:

Bornscheuer Drexler Eisele, Stuttgart

Mechanical Engineering:

Paul+Gample+Partner, Esslingen am Neckar

Competition:

Competition Hospitalhof 2009 – 1st prize

Construction period:

2015-2017

Gross floor area:

700 square meters

Effective Area:

355 square meters

Location:

Büchsenstrasse 33, 70174 Stuttgart, Germany

Publications

Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei 2

Lederer, Arno / Ragnarsdóttir, Jórunn / Oei, Marc (Hg.)

Jovis Verlag Berlin 2021

Amber Sayah (Hg.):

Architekturstadt Stuttgart

Chr. Belser Gesellschaft für Verlagsgeschäfte GmbH & Co. KG in Kooperation mit der Stuttgarter Zeitung Stuttgart 2018

ISBN 978-3-7630-2803-0

Der Architekt

6 | 2017

VD el Mercurio

6 | 2017

AIT

5 | 2017

Stuttgarter Zeitung

02.03.2017

Photos

Roland Halbe, Stuttgart, Germany